Which? Who? What? Why Award Selection is Critical to Driving Engagement

Quick Jump to Article Contents

For the full white paper, click here.

By Allan Schweyer, Chair, Enterprise Engagement Alliance

Each year in the United States, organizations spend tens of billions of dollars on cash and non-cash rewards for consumer, distributor, sales and employee incentive programs –merchandise, gift cards, group and individual travel programs, time off, cash, etc. But few organizations invest the necessary time to understand which rewards should be used for which people to encourage what outcomes.

Recently, the Enterprise Engagement Alliance (EEA) performed a review of the past quarter-century of research into Rewards & Recognition. Among the main objectives of this review was to determine links between the use of Incentives and Engagement. Looking at evidence from more than forty studies, researchers found that incentive and reward programs can drive engagement if they are carefully and deliberately designed to do so.

Design, in this case, refers to the selection, mix and delivery of rewards, incentives and recognition depending on the target recipients, resources available and the desired outcomes. In much the same way an advertiser crafts the message and selects the media to reach his intended audience, incentive planners must design rewards for the specific recipient. Only by these means can rewards strike at the emotional heart of the matter and deliver ROI in excess of the cost of the reward.

A LINK TO BROADER OBJECTIVES

The day when rewards and incentives were best delivered in a “one-size-fits-all” format has long passed. The plain truth is that different rewards drive different behaviors and outcomes. Customers, for example, have become more engaged and loyal through targeted, tangible rewards programs, as well as through forms of recognition that strengthen their emotional connection to a vendor and its brand.

More importantly, rewards and incentives programs must demonstrably link “incentivized” behaviors and actions to broader organizational objectives. In a recent study of 2,000 organizations across the United States, a close connection between incentives and corporate goals was the most powerful of 30 human capital management best practices studied. Where the link was strong and visible, organizations were more than twice as likely to fall into the study’s highest quartile in financial performance over the previous seven years.

White paper sponsored by:

|

Reward Selection Pointers

Make a clear distinction between compensation and recognition. Select rewards that can’t in any way be confused with pay, commissions, or pricing so that the recipient understands that the reward represents recognition, not compensation.

Tailor reward selections to your audience. Make a point of selecting rewards that reflect the lifestyles and demographics of your audience so that participants feel a personal connection with the rewards program.

Pay attention to presentation. Make the most of the reward-giving process by customizing or personalizing the presentation.

|

THE MAIN DECISION

Rewards and incentives come in many varieties. The possibilities are nearly endless, but the main decision for most incentive program designers boils down to cash vs. non-cash rewards. The implications of this decision can be significant. While cash is frequently among the most preferred rewards among recipients, it is rarely the most strategic choice for the planner. Research from the IRF and other sources has consistently measured greater impact and Return on Investment (ROI) of thoughtful non-cash rewards than cash rewards.

In short, cash does little to associate positive emotional connection (or engagement) with award winners. Carefully selected and presented merchandise or incentive travel, on the other hand, can leave memorable impressions both with the recipient and his or her influencers (i.e. spouse or parents). And when, for example, it is presented by the boss or comes with a note from the CEO, recognition is added to reward (as opposed to being selected from a catalogue and delivered by mail, for instance).

ART AND SCIENCE

The art and science of incentive program design has evolved with the research and continues to adapt to the new realities of today’s workforce, consumer preferences and an ever-shifting business environment.

Incentive plan designers have a great deal more to consider when building their programs than types of rewards alone. Determining the right mix of tangible, intangible, cash and non-cash rewards is equally important, and that requires starting with the source – the challenge the incentive is intended to address.

Planners should examine the basic issue, which is most likely a shortcoming in performance or a goal not being met. An analysis might indicate that a performance gap is caused by a deficiency in knowledge or skills. In this case, incentives are unlikely to be the best method of closing the gap (training may be). Where the gap involves people who are capable of achieving the goal but don’t want to, carefully designed incentives are often a good choice. In these circumstances, planners should understand why people don’t want to do the work (or buy the product as the case may be). Poor product sales might result from confusing marketing, just as work avoidance might come from poor instructions.

Incentive planners should view their role in the context of the bigger picture. They wield a lever that may or may not have a role to play in any particular problem. In many cases, incentives will be part of a mix of “interventions” used to close a performance gap. Each element of the intervention – including communication, training, incentives, etc. – should be directly tied to a corporate goal or objective, and the connection should be easily understood by a stakeholder. Employees who are avoiding tasks will be much more powerfully motivated if they can see how that task impacts bigger, more inspiring goals. Thus, the incentive should relate to the inspiring goal even though it may be rewarded for performing the mundane task.

MODELS OF MOTIVATION

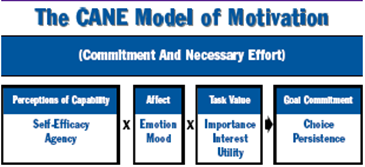

A significant amount of research has been, and continues to be, conducted into the question of what motivates us. Most models and theories view motivation as a continuum in which the right ingredients have to be in place for a level of motivation and commitment to be maintained. The CANE (Commitment And Necessary Effort) model is among the earliest of the modern models. Like those that have been adapted from it, this model emphasizes the emotional aspects of engagement.

The CANE Model

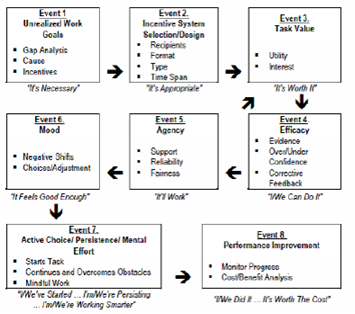

The CANE model gives incentive plan designers guidance in the thought patterns of individuals and what motivates them. Unfortunately, it offers little specific advice on how to design incentive programs. In 2002, researchers Stolovitch, Clark and Condly

developed the PIBI (Performance Improvement By Incentives) model based on the CANE model.

The PIBI Model

The PIBI model was designed to identify the areas of importance and relevance, provide guidance on the step-by-step procedures of implementation and allow decision makers to troubleshoot and correct the system if it is not yielding desired results.

For incentive program designers, even the more detailed PIBI model can leave some doubt as to how to design highly individualized and targeted incentive programs. Where employees are concerned, the Incentive-Engagement Model offers additional guidance. This model is derived from Dan Pink’s research in Drive, his 2010 book on motivating the modern workforce.

The Incentive-Engagement Model

The Incentive-Engagement Model adds the consideration of adverse impact to the designer’s template. Though not the subject of this paper, designers should think about the impact of incentive programs on other parts of the business, especially when forecasting ROI.

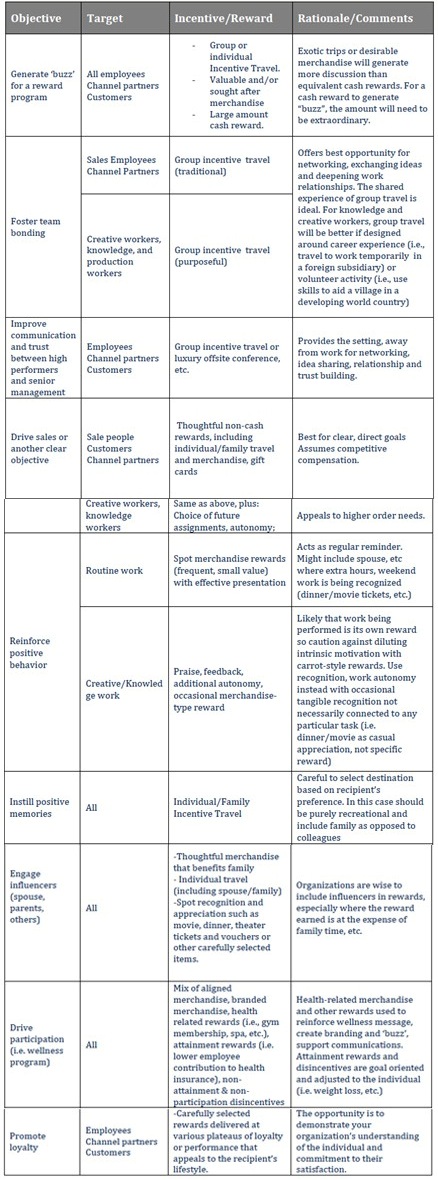

THE DECISION GRID

Incentive program designers might benefit from examples based on objectives that are common to many programs. Below is a simple decision grid that borrows from the research findings, models and best practices in reward selection and program design. There are countless other examples that might be used, but the objectives below (in this case aimed at employees) serve to illustrate the logic.

Rewards Selection Grid

MORE, MORE, MORE

In the planning and programming of incentives that drive engagement, designers are likely to face more scrutiny, more demand for a business case and more evidence of ROI and business impact than they were a decade ago. Though a weak economy and reduced budgets haven’t impacted rewards budgets dramatically, they have in many organizations led to the greater involvement of procurement departments and the CFO in decision-making. The bottom line is that today’s business and work environment demands more sophistication and thought in incentive program design.

In-depth attention to incentive program design has become essential for several other reasons. First and foremost, it recognizes that there are no “one-size-fits-all” solutions for reward recipients. What motivates and engages one person may have the opposite effect on another. Achieving more with less – stretching the incentive budget – is another driver. Twenty-five years of research has shown that well designed programs are much more likely to generate high returns on investment than are less considered approaches.

Careful selection of rewards and continuity of incentive programs are critical in developing a culture of recognition to drive higher levels of engagement and performance. The research summarized in this report represents just the tip of the iceberg in the evidence for targeted rewards, individual incentive plans and flexibility. Incentive program designers that embrace these philosophies will deliver greater impact and ROI to their firms at lower program costs than those who continue to rely on instinct and assumptions.